Relationship between circulating trans-fatty acids and total PSA concentration in elderly men based on the NHANES database

-

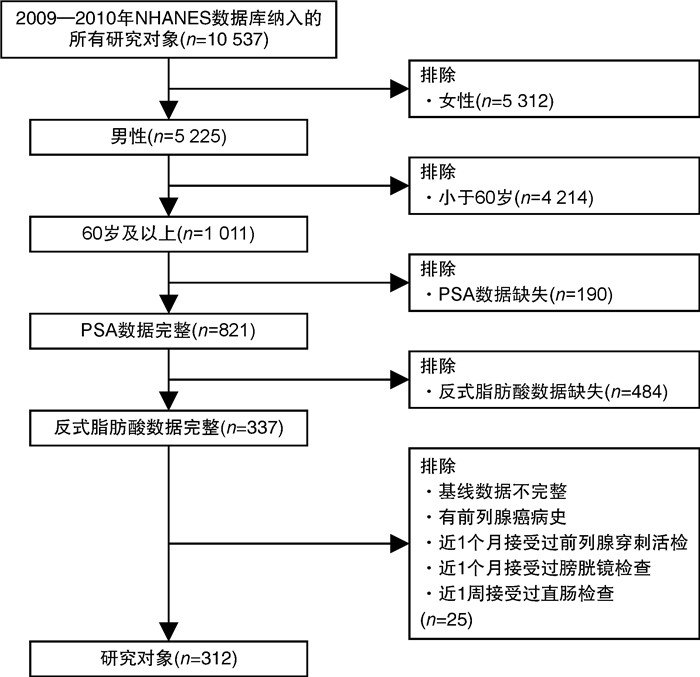

摘要: 目的 越来越多的证据表明反式脂肪酸(trans-fatty acids,TFAs)会影响人们的健康状况。然而,循环TFA浓度与总前列腺特异性抗原(prostate-specific antigen,PSA)之间是否存在关系尚不清楚。因此,本文在美国国家健康与营养调查(National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey,NHANES)数据库的基础上进行了一项横断面人群研究,以分析血浆TFAs和总PSA浓度之间的关系。方法 经过筛选,从NHANES数据库2009-2010年周期中纳入312名参与者。采用单变量、多变量线性回归模型和分层分析检验血浆TFAs(棕榈反油酸、反式异油酸、反油酸、反式亚油酸)浓度与血清总PSA浓度的相关性。结果 在充分调整混杂变量后,数据显示,在老年男性患者中每增加1个单位的log2转换的反式亚油酸,总PSA浓度增加1.14 ng/mL(P < 0.05)。然而棕榈反油酸、反式异油酸、反油酸与总PSA浓度无相关性。此外,分层分析显示反式亚油酸与总PSA浓度的相关性在无体力活动参与者间存在显著差异,表明这种正相关性与参与者无体力活动显著相关(交互作用检验P < 0.05)。结论 总PSA浓度的升高与上升的循环反式亚油酸浓度相关。这种关系在无体力活动的患者中被进一步放大。因此,反式脂肪酸的摄入可能会导致正常人患前列腺癌的风险增高,尤其是在无体力活动的人群里。减少反式脂肪酸的摄入,有助于身体健康。

-

关键词:

- 反式脂肪酸 /

- 总前列腺特异性抗原浓度 /

- 美国国家健康与营养调查数据库 /

- 横断面研究

Abstract: Objective There is increasing evidence revealing that trans-fatty acids(TFAs) contribute to poor health. However, whether there is relationship between circulating TFAs and prostate-specific antigen(PSA) remains unclear. Herein, we conduct a cross-sectional population study to analyze the association between circulating TFAs and total PSA concentrations on the basis of the US. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey(NHANES) database.Methods After conducting the screening, 312 participants fit into our study from NHANES(2009-2010). The univariate and multivariable linear regression model and stratified analysis were used to test the association between concentrations of circulating TFAs(palmitelaidic acid, vaccenic acid, elaidic acid and linoelaidic acid) and total PSA concentration.Results After fully adjustment for confounding variables, the data revealed that the total PSA concentration increased by 1.14 ng/mL for each additional unit of log2-linoelaidic with P < 0.05. However, there was no association between palmitelaidic acid, vaccenic acid, elaidic acid and total PSA concentration. In further stratified analysis, positive association between linoelaidic acid and total PSA was observed in participants with no physical activity with statistical significance.Conclusion Increased total PSA concentration was associated with elevated linoelaidic acid concentration. The relationship was further amplified in patients with no physical activity. Therefore, TFAs intake may contribute to the increased risk of prostate cancer in normal individuals, especially in participants with no physical activity. Reducing the intake of TFAs, could contribute to a healthy body. -

-

表 1 TFAs和总PSA浓度之间的关联

TFAs 模型1 β 模型2 β 模型3 β 95%CI P值 95%CI P值 95%CI P值 棕榈反油酸 0.44(-0.17~1.05) 0.162 2 0.43(-0.20~1.06) 0.180 1 0.52(-0.18~1.23) 0.147 7 反式异油酸 0.08(-0.45~0.61) 0.772 6 0.16(-0.38~0.70) 0.566 0 0.16(-0.44~0.76) 0.594 6 反式油酸 0.18(-0.35~0.71) 0.501 8 0.18(-0.36~0.72) 0.510 1 0.25(-0.38~0.87) 0.444 0 反式亚油酸 0.72(0.05~1.38) 0.035 3 0.88(0.21~1.55) 0.010 7 1.14(0.35~1.93) 0.004 9 表 2 纳入人群基线信息

例(%),X±S 基线特征 反式亚油酸 P值 Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 例数 78 78 78 78 年龄/岁 70.88±6.97 69.96±6.89 69.58±6.59 69.69±7.03 0.628 种族 0.039 墨西哥裔美国人 5(6.41) 7(8.97) 14(17.95) 13(16.67) 其他拉美裔 5(6.41) 5(6.41) 10(12.82) 6(7.69) 非西班牙裔白种人 45(57.69) 50(64.10) 45(57.69) 48(61.54) 非西班牙裔黑种人 14(17.95) 10(12.82) 8(10.26) 10(12.82) 其他种族 9(11.54) 6(7.69) 1(1.28) 1(1.28) 教育水平 0.119 高中以下 23(29.49) 25(32.05) 30(38.46) 24(30.77) 高中 10(12.82) 12(15.38) 19(24.36) 20(25.64) 高中以上 45(57.69) 41(52.56) 29(37.18) 34(43.59) 贫困收入比 2.79±1.57 2.83±1.52 2.71±1.52 2.77±1.55 0.971 尿酸/(μmol/L) 359.86±70.97 370.76±67.81 371.37±81.84 394.17±81.60 0.039 甘油三酯/(mmol/L) 0.90±0.27 1.13±0.35 1.50±0.62 2.16±1.52 < 0.001 BMI/(kg/m2) 27.37±5.90 27.51±4.58 30.28±6.10 29.92±5.01 < 0.001 体力活动 0.709 无体力活动 20(25.64) 27(34.62) 27(34.62) 29(37.18) 低强度体力活动 40(51.28) 32(41.03) 36(46.15) 35(44.87) 高强度体力活动 18(23.08) 19(24.36) 15(19.23) 14(17.95) 吸烟100支烟以上 0.439 是 42(53.85) 47(60.26) 46(58.97) 52(66.67) 否 36(46.15) 31(39.74) 32(41.03) 26(33.33) 1年至少喝12杯酒 0.050 是 54(69.23) 65(83.33) 66(84.62) 65(83.33) 否 24(30.77) 13(16.67) 12(15.38) 13(16.67) 高血压 0.151 是 46(58.97) 51(65.38) 41(52.56) 54(69.23) 否 32(41.03) 27(34.62) 37(47.44) 24(30.77) 糖尿病 0.302 是 15(19.23) 13(16.67) 22(28.21) 21(26.92) 否 61(78.21) 63(80.77) 51(65.38) 53(67.95) 边界线 2(2.56) 2(2.56) 5(6.41) 4(5.13) 表 3 反式亚油酸与总PSA之间的分层分析

项目 模型1 β 模型2 β 模型3 β 95%CI P值 95%CI P值 95%CI P值 种族分层 墨西哥裔美国人 0.22(-0.70~1.14) 0.641 3 0.19(-0.79~1.18) 0.703 6 0.86(-0.64~2.35) 0.272 1 其他拉美裔 3.27(-1.55~8.09) 0.195 5 3.70(-1.10~8.51) 0.146 6 6.89(0.96~12.83) 0.046 1 非西班牙裔白种人 0.71(-0.13~1.54) 0.099 1 0.89(0.05~1.73) 0.039 6 1.09(0.10~2.07) 0.031 7 非西班牙裔黑种人 0.40(-0.39~1.20) 0.329 5 0.41(-0.32~1.15) 0.277 6 0.53(-0.47~1.52) 0.310 2 其他种族 -0.84(-4.11~2.44) 0.623 7 -0.04(-3.87~3.80) 0.985 5 11.41(-34.55~57.36) 0.711 7 交互作用检验P值 0.231 6 0.136 8 0.002 7 BMI分层 < 25 kg/m2 3.26(1.58~4.94) 0.000 3 3.02(1.40~4.65) 0.000 5 1.70(-0.49~3.89) 0.131 8 25~30 kg/m2 0.20(-0.77~1.17) 0.687 7 0.38(-0.58~1.34) 0.436 0 0.22(-1.04~1.49) 0.729 0 >30 kg/m2 -0.20(-0.88~0.47) 0.560 8 -0.08(-0.79~0.64) 0.834 9 0.10(-0.81~1.00) 0.835 9 交互作用检验P值 0.000 1 0.000 1 0.174 1 体力活动分层 无体力活动 2.17(0.64~3.71) 0.006 6 2.80(1.26~4.33) 0.000 6 2.35(0.48~4.21) 0.015 7 低强度体力活动 -0.39(-1.08~0.30) 0.270 4 -0.32(-1.06~0.42) 0.401 2 -0.10(-1.03~0.84) 0.841 0 高强度体力活动 0.40(-0.81~1.61) 0.515 4 0.60(-0.65~1.84) 0.350 3 0.66(-0.91~2.24) 0.411 4 交互作用检验P值 0.003 5 0.000 1 0.021 7 -

[1] Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, et al. Cancer statistics, 2022[J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2022, 72(1): 7-33. doi: 10.3322/caac.21708

[2] Grammatikopoulou MG, Gkiouras K, Papageorgiou SΤ, et al. Dietary factors and supplements influencing prostate specific-antigen(PSA)concentrations in men with prostate cancer and increased cancer risk: an evidence analysis review based on randomized controlled trials[J]. Nutrients, 2020, 12(10): 2985. doi: 10.3390/nu12102985

[3] Moul JW, Walsh PC, Rendell MS, et al. Re: early detection of prostate cancer: AUA guideline: H.B. Carter, P.C. albertsen, M.J. Barry, R. etzioni, S.J. freedland, K.L. Greene, L. holmberg, P. kantoff, B.R. konety, M.H. Murad, D.F. penson and A.L. zietman J Urol 2013;190: 419-426[J]. J Urol, 2013, 190(3): 1134-1137. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.07.002

[4] Ilic D, Djulbegovic M, Jung JH, et al. Prostate cancer screening with prostate-specific antigen(PSA)test: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. BMJ, 2018, 362: k3519.

[5] Tan GH, Nason G, Ajib K, et al. Smarter screening for prostate cancer[J]. World J Urol, 2019, 37(6): 991-999. doi: 10.1007/s00345-019-02719-5

[6] Han PKJ, Kobrin S, Breen N, et al. National evidence on the use of shared decision making in prostate-specific antigen screening[J]. Ann Fam Med, 2013, 11(4): 306-314. doi: 10.1370/afm.1539

[7] Fenton JJ, Weyrich MS, Durbin S, et al. Prostate-specific antigen-based screening for prostate cancer[J]. JAMA, 2018, 319(18): 1914. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.3712

[8] Misra-Hebert AD, Hu B, Klein EA, et al. Prostate cancer screening practices in a large, integrated health system: 2007-2014[J]. BJU Int, 2017, 120(2): 257-264. doi: 10.1111/bju.13793

[9] Liu ZC, Chen C, Yu FX, et al. Association of total dietary intake of sugars with prostate-specific antigen(PSA)concentrations: evidence from the national health and nutrition examination survey(NHANES), 2003-2010[J]. Biomed Res Int, 2021, 2021: 4140767.

[10] Lichtenstein AH. Dietary trans fatty acids and cardiovascular disease risk: past and present[J]. Curr Atheroscler Rep, 2014, 16(8): 433. doi: 10.1007/s11883-014-0433-1

[11] Wanders AJ, Zock PL, Brouwer IA. Trans fat intake and its dietary sources in general populations worldwide: a systematic review[J]. Nutrients, 2017, 9(8): 840. doi: 10.3390/nu9080840

[12] Calder PC. Functional roles of fatty acids and their effects on human health[J]. J Parenter Enteral Nutr, 2015, 39(1S): 18S-32S.

[13] Wang QY, Imamura F, Lemaitre RN, et al. Plasma phospholipid trans-fatty acids levels, cardiovascular diseases, and total mortality: the cardiovascular health study[J]. J Am Heart Assoc, 2014, 3(4): e000914. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.000914

[14] Mozaffarian D, Aro A, Willett WC. Health effects of trans-fatty acids: experimental and observational evidence[J]. Eur J Clin Nutr, 2009, 63(Suppl 2): S5-S21.

[15] Hu JF, La Vecchia C, de Groh M, et al. Dietary transfatty acids and cancer risk[J]. Eur J Cancer Prev, 2011, 20(6): 530-538. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0b013e328348fbfb

[16] Liss MA, Al-Bayati O, Gelfond J, et al. Higher baseline dietary fat and fatty acid intake is associated with increased risk of incident prostate cancer in the SABOR study[J]. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis, 2019, 22(2): 244-251. doi: 10.1038/s41391-018-0105-2

[17] Kim OY, Lee SM, An WS. Impact of blood or erythrocyte membrane fatty acids for disease risk prediction: focusing on cardiovascular disease and chronic kidney disease[J]. Nutrients, 2018, 10(10): 1454. doi: 10.3390/nu10101454

[18] Valenzuela CA, Baker EJ, Miles EA, et al. Eighteen carbon trans fatty acids and inflammation in the context of atherosclerosis[J]. Prog Lipid Res, 2019, 76: 101009. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2019.101009

[19] Lagerstedt SA, Hinrichs DR, Batt SM, et al. Quantitative determination of plasma c8-c26 total fatty acids for the biochemical diagnosis of nutritional and metabolic disorders[J]. Mol Genet Metab, 2001, 73(1): 38-45. doi: 10.1006/mgme.2001.3170

[20] Gudmundsson J, Sigurdsson JK, Stefansdottir L, et al. Genome-wide associations for benign prostatic hyperplasia reveal a genetic correlation with serum levels of PSA[J]. Nat Commun, 2018, 9(1): 4568. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06920-9

[21] Kristal AR, Chi C, Tangen CM, et al. Associations of demographic and lifestyle characteristics with prostate-specific antigen(PSA)concentration and rate of PSA increase[J]. Cancer, 2006, 106(2): 320-328. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21603

[22] Zhao Y, Zhang YT, Wang X, et al. Relationship between body mass index and concentrations of prostate specific antigen: a cross-sectional study[J]. Scand J Clin Lab Invest, 2020, 80(2): 162-167. doi: 10.1080/00365513.2019.1703217

[23] Mantovani A. Plasma trans-fatty acid and risk of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: new data from National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey(NHANES) [J]. Int J Cardiol, 2018, 272: 329-330. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.07.136

[24] Wang XQ, Jiang FJ, Chen WQ, et al. The association between circulating trans fatty acids and thyroid function measures in U.S. adults[J]. Front Endocrinol, 2022, 13: 928730. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2022.928730

[25] Wei CC, Chen YM, Yang Y, et al. Assessing volatile organic compounds exposure and prostate-specific antigen: national Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2001-2010[J]. Front Public Health, 2022, 10: 957069. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.957069

[26] Tian XY, Xue BD, Wang B, et al. Physical activity reduces the role of blood cadmium on depression: a cross-sectional analysis with NHANES data[J]. Environ Pollut, 2022, 304: 119211. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2022.119211

[27] de Souza RJ, Mente A, Maroleanu A, et al. Intake of saturated and trans unsaturated fatty acids and risk of all cause mortality, cardiovascular disease, and type 2 diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies[J]. BMJ, 2015, 351: h3978.

[28] Liu X, Schumacher FR, Plummer SJ, et al. Trans-fatty acid intake and increased risk of advanced prostate cancer: modification by RNASEL R462Q variant[J]. Carcinogenesis, 2007, 28(6): 1232-1236. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm002

[29] Chowdhury R, Warnakula S, Kunutsor S, et al. Association of dietary, circulating, and supplement fatty acids with coronary risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Ann Intern Med, 2014, 160(6): 398-406. doi: 10.7326/M13-1788

[30] Kim J, Coetzee GA. Prostate specific antigen gene regulation by androgen receptor[J]. J Cell Biochem, 2004, 93(2): 233-241. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20228

[31] Ueda T, Mawji NR, Bruchovsky N, et al. Ligand-independent activation of the androgen receptor by interleukin-6 and the role of steroid receptor coactivator-1 in prostate cancer cells[J]. J Biol Chem, 2002, 277(41): 38087-38094. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203313200

[32] Dagar M, Singh JP, Dagar G, et al. Phosphorylation of HSP90 by protein kinase A is essential for the nuclear translocation of androgen receptor[J]. J Biol Chem, 2019, 294(22): 8699-8710. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA119.007420

[33] Oteng AB, Kersten S. Mechanisms of action of trans fatty acids[J]. Adv Nutr, 2020, 11(3): 697-708. doi: 10.1093/advances/nmz125

[34] Bernal-Soriano MC, Lumbreras B, Hernández-Aguado I, et al. Untangling the association between prostate-specific antigen and diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Clin Chem Lab Med, 2020, 59(1): 11-26.

[35] Belladelli F, Montorsi F, Martini A. Metabolic syndrome, obesity and cancer risk[J]. Curr Opin Urol, 2022, 32(6): 594-597. doi: 10.1097/MOU.0000000000001041

[36] Mansor R, Holly J, Barker R, et al. IGF-1 and hyperglycaemia-induced FOXA1 and IGFBP-2 affect epithelial to mesenchymal transition in prostate epithelial cells[J]. Oncotarget, 2020, 11(26): 2543-2559. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.27650

[37] Johnson RJ, Perez-Pozo SE, Sautin YY, et al. Hypothesis: could excessive fructose intake and uric acid cause type 2 diabetes?[J]. Endocr Rev, 2009, 30(1): 96-116.

-

下载:

下载: